Expanding across Europe is a major milestone for any merchant, and selecting the right Payment Service Provider (PSP) is a critical decision. Many providers advertise “full European coverage”, claiming to be licensed to operate in all 27 EU member states. This is typically achieved through the EU’s passporting system, which allows a licence from a single “home” country to be extended across the entire bloc.

On the surface, this appears to solve the problem. In practice, however, it often masks a significant gap between legal compliance and operational capability.

Our analysis, based on the Payments Ecosystem Directory (PED)—a comprehensive database mapping PSP licences, operational regions, and capabilities—reveals what this gap looks like from a data perspective. These findings align with trends highlighted by EU regulatory bodies.

The PED is designed to help merchants and industry stakeholders make informed decisions by providing granular insights into PSP strategies, licence distribution, and operational reach. It goes beyond simple passporting claims, enabling businesses to verify whether a provider can truly support their needs in specific markets.

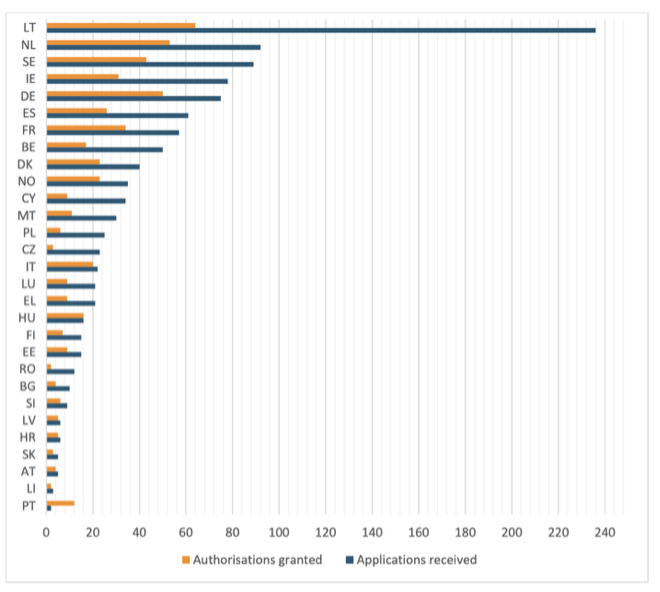

Our analysis focused on “super-passporters”, PSPs that hold a primary licence (PI or EMI) in one EU country and passport it to more than 20 others. The distribution of these licences is heavily concentrated in a few jurisdictions:

.png)

This concentration is no coincidence. It reflects deliberate strategic choices by providers, typically following one of two models.

Jurisdictions such as Lithuania actively attract fintechs through what the Oxford Business Law Blog calls “full-blown regulatory competition”. The Bank of Lithuania, for example, is widely cited for its fast licensing process—sometimes as quick as three months—and direct access to the EU’s SEPA payment system via its CENTROlink infrastructure.

Other jurisdictions, like Ireland and the Netherlands, compete on different terms. Ireland offers a stable common law system, a deep talent pool, and a favourable 12.5% corporate tax rate. Crucially, the Central Bank of Ireland enforces substance requirements, expecting the core of the business to be physically located in the country. The Netherlands is known for its fair yet strict regulatory approach and is highly regarded across the industry.

Both strategies are valid for PSPs. The risk for merchants arises when a provider’s strategy does not align with their operational needs.

The EU’s passporting system operates on a home state supervision principle. This means the regulator in the home country (e.g., Lithuania) is solely responsible for supervising that firm’s activities across all host countries (e.g., Germany, France, Spain).

This creates a practical risk for merchants. For example, a German business accustomed to working with BaFin may find that, in the event of a dispute or compliance issue, BaFin has limited jurisdiction over a provider licensed in Lithuania. Instead, the merchant is reliant on the supervisory resources and priorities of a foreign regulator with which they have no prior relationship.

In June 2023, businesses using the Lithuanian-licensed EMI PAYRNET learned this lesson the hard way. When the Bank of Lithuania revoked PAYRNET’s licence for “serious, systematic” AML violations, the impact was immediate. Regulators had to intervene to compel the firm to return client funds. As reported by The Fintech Times, fintechs and card programme managers relying on PAYRNET’s infrastructure were left unable to serve their customers, resulting in lost trust and revenue.

Merchants became collateral damage in a cross-border regulatory crackdown and operations halted overnight because their provider’s “speed-to-market” licence failed under scrutiny.

This concentration is explained by other data in the report (see Figure 1), which shows a wide variation in the amount of licenses received and authorisations granted. It visually confirms the skew towards specific jurisdictions, validating the concentration of “super-passporters identified in our database.

The European Banking Authority (EBA) has repeatedly flagged this risk. Its 2023 report on AML/TF risks in the payments sector noted:

“…payment institutions with weak AML/CFT controls operate in the EU and may establish themselves in Member States where the authorisation process is perceived as less stringent to passport their activities cross-border afterwards.”

This confirms what industry insiders already know: firms often select their home regulator based on speed rather than substance. The result? A race to the bottom, where countries compete by lowering compliance standards—placing the cost on consumers and businesses.

For merchants, asking “Do you have a European licence?” is no longer enough. Instead, due diligence should include:

A legal passport gives a PSP the right to operate. Demonstrating these capabilities proves they can be a reliable partner. Verifying these responses against the Payments Ecosystem Directory will significantly accelerate this process and reduce risk.

The Payments Ecosystem Directory is a trusted resource for merchants seeking clarity in a complex market. It provides verified data on PSP licences, operational regions, and capabilities—empowering businesses to make informed decisions and avoid costly mistakes.

In this article, we will review the latest developments in agentic commerce from a merchant perspective. We will compare user journeys, potential challenges, implementation models and value creation opportunities.

.png)

The future of fintech isn’t arriving, it’s already here. In Payments Pulse 2025, PaymentGenes explores how Open Finance, real-time payments, ESG, fraud innovation, and fintech M&A are no longer siloed topics; they’re intersecting forces shaping the next era of financial services.